Abstract: Womenís weight and body composition is significantly influenced by the female sex-steroid hormones. Levels of these hormones fluctuate in a defined manner throughout the menstrual cycle and interact to modulate energy homeostasis. This paper reviews the scientific literature on the relationship between hormonal changes across the menstrual cycle and components of energy balance, with the aim of clarifying whether this influences weight loss in women. In the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle it appears that womenís energy intake and energy expenditure are increased and they experience more frequent cravings for foods, particularly those high in carbohydrate and fat, than during the follicular phase. This suggests that the potential of the underlying physiology related to each phase of the menstrual cycle may be worth considering as an element in strategies to optimize weight loss. Studies are needed to assess the weight loss outcome of tailoring dietary recommendations and the degree of energy restriction to each menstrual phase throughout a weight management program, taking these preliminary findings into account.

Background

Compared to men, women get the short end of the stick in almost everything related to body composition. Their bodies fight back harder, they lose both weight and fat slower (even given an identical intervention), they gain muscle more slowly, etc. Then again, they do get that whole multiple orgasm thing so there is at least some good that comes along with the bad.

In any case, there are a lot of potential reasons for things to be this way and itís been theorized that the importance of women in keeping humanity alive (by raising children) during famines is a huge part of the gender discrepancy. For example, women are more likely to be in the super-obese category and far more likely to survive famines than men. While even menís bodies fight back, the simple fact is that womenís pretty much always fight back more.

Of course, the biggest potential impact on all of this is hormones which differ drastically between men and women. Itís been known for a while that womenís fuel utilization changes during their menstrual cycle, as does appetite and potentially energy expenditure.

In this vein, itís been suggested that dieting (and training) might or should be modified during the menstrual cycle to match up physiologically with what is going on in a womanís body; Iíll come back to this a bit below.

Thatís what todayís research review is about, a look at how things such as energy intake, appetite, energy expenditure and body weight change throughout a womanís cycle, as well the impact of birth control is briefly examined along with some issues related to PMS and food cravings.

The Paper

The first section of the paper is simply a review of the hormonal changes which occur during a normal menstrual cycle. Although there is variability, the typical womanís full cycle is 28 days (this is an average) which is typically divided up into 4 distinct phases. With menstruation taken as day 1, we can define early follicular phase (day 1-4), late follicular (days 5-11), periovulation (day 12-15), and luteal phase (days 16-28).

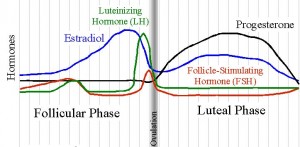

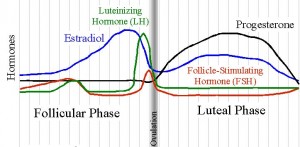

A number of hormones change during the cycle but the two that Iím going to focus on are estrogen and progesterone. During the early follicular phase, both estrogen and progesterone are relatively low. Estrogen (estradiol in the graphic below) shows a peak in the late follicular phase followed by a drop. Progesterone starts a slow increase through ovulation and both estrogen/progesterone peak in the middle of the luteal phase before returning to baseline.

The paper notes that body temperature typically goes up after ovulation (for example, some women try to use changes in body temperature to predict fertility), remains high during the luteal phase before returning to baseline at or after the start of menstruation.

This pattern of hormonal change between estrogen (estradiol) and progesterone is shown in the graphic below. Estradiol is the blue line, progesterone the black line. You neednít worry about the green and red lines (LH and FSH respectively) within the context of todayís research review.

Click to view a larger version

Click to view a larger version

The paper then examined research on energy (food) intake during different parts of the menstrual cycle. In animals, energy intake is reduced at ovulation (when estrogen peaks) and increases after ovulation when progesterone is peaking; this has long been interpreted as indicating that progesterone drove food intake.

Research in humans has generally borne out that pattern, higher energy intakes during the luteal phase and lower intakes during the follicular phase; the increase in food intake has generally been reported to be between 90-500 calories day.

Itís interesting to note that some research suggests that it is falling estrogen rather than increasing progesterone that drives hunger. As I discussed in the research review on Crosstalk Between Estrogen and Leptin Signalling in the Hypothalamus, estrogen appears to either improve leptin signalling in the brain or send a leptin-like signal to the brain directly; falling estrogen would reduce overall signalling which would tend to facilitate hunger.

Of course, there is also some reason to think that itís a combination effect of estrogen and progesterone that is having the overall effect. Given everything thatís changing at once, it is often difficult to determine exactly which hormone (or how they are interacting) is having a specific effect.

Tangentially, the paper mentions that estrogens might play an important role for weight and fat loss loss through inhibition of food intake. Iíd also mention that a good bit of data suggests that estrogen is actually lipolytic, helping to mobilize fatty acids during aerobic activities. In fact, if you inject men with estrogen, they will mobilize fatty acids more effectively as well.

Itís actually even more complicated than this and estrogen can be seen to be having both positive and negative effects on fat loss (and regional fat loss). I discuss this in more detail in The Stubborn Fat Solution; sufficed to say that idea that Ďestrogen is badí in terms of fat loss is a simplistically incorrect one.

I bring this up for a couple of reasons. Itís interesting to note that with increasing fat loss, estrogen levels typically drop, this is probably part of what drives hunger in women as they get leaner (Iíd note that falling estrogen certainly doesnít seem to make lower body fat mobilization any easier for female dieters which I think throws a major wrench in the idea that estrogen is responsible for womenís hip/thigh fat).

As well, there is an idea that comes up among some female dieters of wanting to Ďbanish estrogení for a variety of reasons (whether fat loss or otherwise). Given that estrogen may be doing many beneficial things in terms of fat loss, this idea is probably going to do more harm than good. Iíd also mention that low estrogen causes major problems with bone density, trying to get rid of it will cause major problems down the road.

Finally, the paper notes that some of the drive for appetite may be mediated by changes in blood glucose homeostasis. Empirically, some women seem to be more prone to hypoglycemia during certain phases of the menstrual cycle and falling blood sugar can stimulate hunger. Ensuring that blood glucose levels stay stable might be extremely beneficial during those periods. For example, consuming moderate amounts of fruit during that part of the cycle (to ensure that there is always some liver glycogen to be released to maintain blood glucose) would be a useful strategy.

The next part of the paper examines changes in macronutrient intake, food cravings and PMS. Studies, as usual, are inconsistent showing variously increases in carb, fat and protein intake during the luteal phase. Some of this may simply be related to being hungrier in general with no clear increase in desire for a specific nutrient.

Some research has indicated that the increase in carbohydrate intake is due to a specific craving although, with chocolate (a combination of carbs, fat and other micronutrients) being the most craved item, other possibilities exist. Cravings for a sugar/fat combo or something else entirely may be functioning here.

Alternately, the issue could simply be one of a magnesium deficiency; some research indicates that magnesium supplements help with PMS related cravings and chocolate tends to be high in magnesium; women may simply be self-medicating an important micronutrient. In this vein, many females report that their cravings are ameliorated if not eliminated when they are supplementing magnesium (e.g. 400 mg of magnesium citrate at bedtime, which can also help with sleep).

Next, the paper looks at the impact of menstrual cycle on energy expenditure (this brings us back to the increased body temperature I noted above). The major increase in energy expenditure occurs also during the luteal phase (when hunger is increased) with increases of 2.5-11.5% having been reported.

Itís important to note that this only amounts to a daily increase in energy expenditure of 90-280 calories per day. That would be contrasted to the potential increase in food intake of 90-500 calories. That is, while energy expenditure is up during the luteal phase, so is appetite; increases in energy intake can easily overwhelm the small increase in energy output if food intake isnít controlled.

The increase in metabolic rate is thought to be primarily related to the increasing progesterone levels. So while increasing progesterone may not be driving the increased appetite, it may be stimulating metabolic rate slightly during the luteal phase.

Next, the study examined the impact of birth control pills on body weight, first pointing out that there a number of different types of birth control containing synthetic estrogen, progesterone or possibly both. I mention this because, given the differences in each of the hormones (and their interactions), it becomes fairly inaccurate to talk about the Ďeffects of birth controlí on any of this; different types are likely to have different effects and this can vary depending on the woman as well.

Studies have examined the impact of birth control on energy intake and several find an increase in both total energy intake and fat intake; others have found no effect. With limited research itís hard to tell if this is an issue of different types of birth control or possibly individual variance. Empirically women seem to respond extremely differently to birth control. Some go crazy, some get suicidal, some gain weight, some donít, etc. etc.

Of course, the same can be said for female responses to the menstrual cycle in general; some have crippling PMS and out of control hunger, others are hit at most mildly or notice almost nothing at all. Differences in hormone levels, sensitivity, etc. all contribute to the mystery that is woman.

As far as energy expenditure, while one study showed a small increase in basal metabolic rate of 5% with birth control intake, others have found no effect. Again, type of pill and individual variance is probably at play here (e.g. you might expect progesterone dominant pills to have the biggest impact on metabolic rate).

Looking at body weight, most studies have apparently reported no substantial change in body weight with birth control pills although many show a trend towards increased body weight. One exception is Depo-Provera injections which are associated with weight gain.

Finally the paper looks at potential implications for dieting and weight loss. The paper argues that considering which phase of the menstrual cycle the female in when starting a diet may be important. They argue that starting the diet premenstrually when hunger and food cravings are most intense may be a bad idea, just from an adherence standpoint.

Instead, starting a diet following menstruation or in the late follicular phase when food cravings and hunger are less may make compliance easier. They also suggest that increasing total energy intake 5-8 days before menstruation (when hunger/energy expenditure are at their highest) may prevent a suboptimal caloric intake (which can make folks lethargic) and help with long term adherence to a diet. While I doubt most females would be willing to break their diet 5-8 days out of every month, at least raising calories slightly to avoid loss of control due to out of control hunger might be a worthwhile consideration.

Of course, itís also easy to look at that from the other direction; in theory at least, keeping calories controlled during periods when energy expenditure is up (for hormonal reasons) might generate superior fat loss. Of course, that also means keeping calories controlled when hunger is at its worst. Life, she is full of compromises.

The paper also argues that as chocolate is seemingly irreplaceable due to cravings, small amounts of dark chocolate should be allowed to improve dietary adherence. Interestingly, I first read that idea in an older book called Why Women Need Chocolate which was an interesting look at the idea of biologically driven food cravings.

Iíd note again that many females note that these types of cravings are almost eliminated if they supplement with magnesium so Iím not sure that the idea that chocolate is irreplaceable is exactly true. Of course, dark cocoa has a lot of health benefits anyhow and there are certainly worth things for a female to consume.

However, given that I wrote a book called A Guide to Flexible Dieting arguing that allowing food flexibility can improve adherence, I think there is a lot of logic in their argument in a general sense. At the end of the day, better to allow a small controlled amount of chocolate than feel deprived and end up eating the entire bag. An extra 100 calories is always better than an extra 1000 calories in the long-term.

The same goes for the increased hunger that occurs when estrogen levels drop in the late follicular phase; if allowing a few hundred extra calories acutely avoids a massive loss of control, that would seem beneficial in the long-term.

Summing Up

So thatís a look at some of the things that can occur (good and bad) in terms of food intake, energy expenditure during the menstrual cycle. It should be obvious that massive changes in hormones, including the interactions between estrogen and progesterone drive a great deal of processes that can impact on a womanís food intake, energy expenditure and, of course, body weight.

Iíd note again that the above processes tend to be exceedingly variable between women and while generalizations can be made from studies, women may need to track things like body temperature, weight and appetite through a couple of months to get an idea of how their bodies respond. Body temperature can be tracked as can things such as training capacity (some women find it very difficult to train effectively during certain periods of their cycle), appetite, etc.

In periods when hunger is off the map and/or blood glucose seems to keep crashing, increasing food intake slightly (and including moderate fruit) may be beneficial. For those women able to keep food intake under control during the part of the cycle when body temperature is up, increased fat loss may be possible.

Supplementing with various nutrients such as magnesium and fish oils seems to help with PMS symptoms and may help with food cravings during particularly difficult periods. Alternately, that may be a good time to include free meals or refeeds as discussed in A Guide to Flexible Dieting; rather than tryingto fight the bodyís tendencies (and losing control completely), finding ways to work with them may be better in terms of long-term results. Allowing controlled amounts of craved foods tends to help avoid problems with guilt and eating the whole box. Just keep it controlled.

Iíd note, in concluding, that other more involved strategies have been suggested from time to time. Things like synchronizing the intake of carbs or fats with different parts of the cycle (e.g. eating relatively more carbs when carb metabolism is dominant and less when fat metabolism is dominant) have been suggested. Iím not sure, practically, how well theyíve panned out but if anybody has any experience with the idea, Iíd love to hear about it in the comments section.

Background

Compared to men, women get the short end of the stick in almost everything related to body composition. Their bodies fight back harder, they lose both weight and fat slower (even given an identical intervention), they gain muscle more slowly, etc. Then again, they do get that whole multiple orgasm thing so there is at least some good that comes along with the bad.

In any case, there are a lot of potential reasons for things to be this way and itís been theorized that the importance of women in keeping humanity alive (by raising children) during famines is a huge part of the gender discrepancy. For example, women are more likely to be in the super-obese category and far more likely to survive famines than men. While even menís bodies fight back, the simple fact is that womenís pretty much always fight back more.

Of course, the biggest potential impact on all of this is hormones which differ drastically between men and women. Itís been known for a while that womenís fuel utilization changes during their menstrual cycle, as does appetite and potentially energy expenditure.

In this vein, itís been suggested that dieting (and training) might or should be modified during the menstrual cycle to match up physiologically with what is going on in a womanís body; Iíll come back to this a bit below.

Thatís what todayís research review is about, a look at how things such as energy intake, appetite, energy expenditure and body weight change throughout a womanís cycle, as well the impact of birth control is briefly examined along with some issues related to PMS and food cravings.

The Paper

The first section of the paper is simply a review of the hormonal changes which occur during a normal menstrual cycle. Although there is variability, the typical womanís full cycle is 28 days (this is an average) which is typically divided up into 4 distinct phases. With menstruation taken as day 1, we can define early follicular phase (day 1-4), late follicular (days 5-11), periovulation (day 12-15), and luteal phase (days 16-28).

A number of hormones change during the cycle but the two that Iím going to focus on are estrogen and progesterone. During the early follicular phase, both estrogen and progesterone are relatively low. Estrogen (estradiol in the graphic below) shows a peak in the late follicular phase followed by a drop. Progesterone starts a slow increase through ovulation and both estrogen/progesterone peak in the middle of the luteal phase before returning to baseline.

The paper notes that body temperature typically goes up after ovulation (for example, some women try to use changes in body temperature to predict fertility), remains high during the luteal phase before returning to baseline at or after the start of menstruation.

This pattern of hormonal change between estrogen (estradiol) and progesterone is shown in the graphic below. Estradiol is the blue line, progesterone the black line. You neednít worry about the green and red lines (LH and FSH respectively) within the context of todayís research review.

Click to view a larger version

Click to view a larger versionThe paper then examined research on energy (food) intake during different parts of the menstrual cycle. In animals, energy intake is reduced at ovulation (when estrogen peaks) and increases after ovulation when progesterone is peaking; this has long been interpreted as indicating that progesterone drove food intake.

Research in humans has generally borne out that pattern, higher energy intakes during the luteal phase and lower intakes during the follicular phase; the increase in food intake has generally been reported to be between 90-500 calories day.

Itís interesting to note that some research suggests that it is falling estrogen rather than increasing progesterone that drives hunger. As I discussed in the research review on Crosstalk Between Estrogen and Leptin Signalling in the Hypothalamus, estrogen appears to either improve leptin signalling in the brain or send a leptin-like signal to the brain directly; falling estrogen would reduce overall signalling which would tend to facilitate hunger.

Of course, there is also some reason to think that itís a combination effect of estrogen and progesterone that is having the overall effect. Given everything thatís changing at once, it is often difficult to determine exactly which hormone (or how they are interacting) is having a specific effect.

Tangentially, the paper mentions that estrogens might play an important role for weight and fat loss loss through inhibition of food intake. Iíd also mention that a good bit of data suggests that estrogen is actually lipolytic, helping to mobilize fatty acids during aerobic activities. In fact, if you inject men with estrogen, they will mobilize fatty acids more effectively as well.

Itís actually even more complicated than this and estrogen can be seen to be having both positive and negative effects on fat loss (and regional fat loss). I discuss this in more detail in The Stubborn Fat Solution; sufficed to say that idea that Ďestrogen is badí in terms of fat loss is a simplistically incorrect one.

I bring this up for a couple of reasons. Itís interesting to note that with increasing fat loss, estrogen levels typically drop, this is probably part of what drives hunger in women as they get leaner (Iíd note that falling estrogen certainly doesnít seem to make lower body fat mobilization any easier for female dieters which I think throws a major wrench in the idea that estrogen is responsible for womenís hip/thigh fat).

As well, there is an idea that comes up among some female dieters of wanting to Ďbanish estrogení for a variety of reasons (whether fat loss or otherwise). Given that estrogen may be doing many beneficial things in terms of fat loss, this idea is probably going to do more harm than good. Iíd also mention that low estrogen causes major problems with bone density, trying to get rid of it will cause major problems down the road.

Finally, the paper notes that some of the drive for appetite may be mediated by changes in blood glucose homeostasis. Empirically, some women seem to be more prone to hypoglycemia during certain phases of the menstrual cycle and falling blood sugar can stimulate hunger. Ensuring that blood glucose levels stay stable might be extremely beneficial during those periods. For example, consuming moderate amounts of fruit during that part of the cycle (to ensure that there is always some liver glycogen to be released to maintain blood glucose) would be a useful strategy.

The next part of the paper examines changes in macronutrient intake, food cravings and PMS. Studies, as usual, are inconsistent showing variously increases in carb, fat and protein intake during the luteal phase. Some of this may simply be related to being hungrier in general with no clear increase in desire for a specific nutrient.

Some research has indicated that the increase in carbohydrate intake is due to a specific craving although, with chocolate (a combination of carbs, fat and other micronutrients) being the most craved item, other possibilities exist. Cravings for a sugar/fat combo or something else entirely may be functioning here.

Alternately, the issue could simply be one of a magnesium deficiency; some research indicates that magnesium supplements help with PMS related cravings and chocolate tends to be high in magnesium; women may simply be self-medicating an important micronutrient. In this vein, many females report that their cravings are ameliorated if not eliminated when they are supplementing magnesium (e.g. 400 mg of magnesium citrate at bedtime, which can also help with sleep).

Next, the paper looks at the impact of menstrual cycle on energy expenditure (this brings us back to the increased body temperature I noted above). The major increase in energy expenditure occurs also during the luteal phase (when hunger is increased) with increases of 2.5-11.5% having been reported.

Itís important to note that this only amounts to a daily increase in energy expenditure of 90-280 calories per day. That would be contrasted to the potential increase in food intake of 90-500 calories. That is, while energy expenditure is up during the luteal phase, so is appetite; increases in energy intake can easily overwhelm the small increase in energy output if food intake isnít controlled.

The increase in metabolic rate is thought to be primarily related to the increasing progesterone levels. So while increasing progesterone may not be driving the increased appetite, it may be stimulating metabolic rate slightly during the luteal phase.

Next, the study examined the impact of birth control pills on body weight, first pointing out that there a number of different types of birth control containing synthetic estrogen, progesterone or possibly both. I mention this because, given the differences in each of the hormones (and their interactions), it becomes fairly inaccurate to talk about the Ďeffects of birth controlí on any of this; different types are likely to have different effects and this can vary depending on the woman as well.

Studies have examined the impact of birth control on energy intake and several find an increase in both total energy intake and fat intake; others have found no effect. With limited research itís hard to tell if this is an issue of different types of birth control or possibly individual variance. Empirically women seem to respond extremely differently to birth control. Some go crazy, some get suicidal, some gain weight, some donít, etc. etc.

Of course, the same can be said for female responses to the menstrual cycle in general; some have crippling PMS and out of control hunger, others are hit at most mildly or notice almost nothing at all. Differences in hormone levels, sensitivity, etc. all contribute to the mystery that is woman.

As far as energy expenditure, while one study showed a small increase in basal metabolic rate of 5% with birth control intake, others have found no effect. Again, type of pill and individual variance is probably at play here (e.g. you might expect progesterone dominant pills to have the biggest impact on metabolic rate).

Looking at body weight, most studies have apparently reported no substantial change in body weight with birth control pills although many show a trend towards increased body weight. One exception is Depo-Provera injections which are associated with weight gain.

Finally the paper looks at potential implications for dieting and weight loss. The paper argues that considering which phase of the menstrual cycle the female in when starting a diet may be important. They argue that starting the diet premenstrually when hunger and food cravings are most intense may be a bad idea, just from an adherence standpoint.

Instead, starting a diet following menstruation or in the late follicular phase when food cravings and hunger are less may make compliance easier. They also suggest that increasing total energy intake 5-8 days before menstruation (when hunger/energy expenditure are at their highest) may prevent a suboptimal caloric intake (which can make folks lethargic) and help with long term adherence to a diet. While I doubt most females would be willing to break their diet 5-8 days out of every month, at least raising calories slightly to avoid loss of control due to out of control hunger might be a worthwhile consideration.

Of course, itís also easy to look at that from the other direction; in theory at least, keeping calories controlled during periods when energy expenditure is up (for hormonal reasons) might generate superior fat loss. Of course, that also means keeping calories controlled when hunger is at its worst. Life, she is full of compromises.

The paper also argues that as chocolate is seemingly irreplaceable due to cravings, small amounts of dark chocolate should be allowed to improve dietary adherence. Interestingly, I first read that idea in an older book called Why Women Need Chocolate which was an interesting look at the idea of biologically driven food cravings.

Iíd note again that many females note that these types of cravings are almost eliminated if they supplement with magnesium so Iím not sure that the idea that chocolate is irreplaceable is exactly true. Of course, dark cocoa has a lot of health benefits anyhow and there are certainly worth things for a female to consume.

However, given that I wrote a book called A Guide to Flexible Dieting arguing that allowing food flexibility can improve adherence, I think there is a lot of logic in their argument in a general sense. At the end of the day, better to allow a small controlled amount of chocolate than feel deprived and end up eating the entire bag. An extra 100 calories is always better than an extra 1000 calories in the long-term.

The same goes for the increased hunger that occurs when estrogen levels drop in the late follicular phase; if allowing a few hundred extra calories acutely avoids a massive loss of control, that would seem beneficial in the long-term.

Summing Up

So thatís a look at some of the things that can occur (good and bad) in terms of food intake, energy expenditure during the menstrual cycle. It should be obvious that massive changes in hormones, including the interactions between estrogen and progesterone drive a great deal of processes that can impact on a womanís food intake, energy expenditure and, of course, body weight.

Iíd note again that the above processes tend to be exceedingly variable between women and while generalizations can be made from studies, women may need to track things like body temperature, weight and appetite through a couple of months to get an idea of how their bodies respond. Body temperature can be tracked as can things such as training capacity (some women find it very difficult to train effectively during certain periods of their cycle), appetite, etc.

In periods when hunger is off the map and/or blood glucose seems to keep crashing, increasing food intake slightly (and including moderate fruit) may be beneficial. For those women able to keep food intake under control during the part of the cycle when body temperature is up, increased fat loss may be possible.

Supplementing with various nutrients such as magnesium and fish oils seems to help with PMS symptoms and may help with food cravings during particularly difficult periods. Alternately, that may be a good time to include free meals or refeeds as discussed in A Guide to Flexible Dieting; rather than tryingto fight the bodyís tendencies (and losing control completely), finding ways to work with them may be better in terms of long-term results. Allowing controlled amounts of craved foods tends to help avoid problems with guilt and eating the whole box. Just keep it controlled.

Iíd note, in concluding, that other more involved strategies have been suggested from time to time. Things like synchronizing the intake of carbs or fats with different parts of the cycle (e.g. eating relatively more carbs when carb metabolism is dominant and less when fat metabolism is dominant) have been suggested. Iím not sure, practically, how well theyíve panned out but if anybody has any experience with the idea, Iíd love to hear about it in the comments section.